Prelude

I must admit, originally I intended this post to be strictly about my market outlook and crypto-mania. However, adding my afterthoughts allowed me to recollect my ideas in ways I otherwise couldn’t have; so in a sense, this post has been much more self-serving. I have two goals: to inform and invoke curiosity. If I can encourage the latter, I will have more than succeeded. If not, at least the efforts were valiant.

“Many shall be restored that are now fallen and many shall fall that are now held in honor” – Horace

Time Travelling

In the Fall of 2017, The Economist released an issue with a captivating title: “The Bull Market in Everything”. As the title implies, the sub-article embodied to a great degree the current market conditions: prices in almost every asset class reaching all-time highs, GDP growth seemingly great and investor psychology relatively optimistic. Add in the then-booming price of Bitcoin and cryptos, you really see why “The Bull Market in Everything” fits the headline.

Skyrocketing prices should warrant caution. The immediate reason for worry are basically twofold. For the past decade, the markets have been prompted by near-zero interest rates through quantitative easing. Only now, has the Fed started to unwind its policies. Along with a (hopefully) gradual interest rate hike, it will begin selling its some $11trn bonds it had previously purchased to re-stabilize the economy. The second, perhaps more worrisome reason, is the increasing degree of euphoria, and progressive pro-risk behaviour that has plagued market participants. At the end of the article, the author ends with words from the Godfather of value investing, Benjamin Graham: margin of safety- which many should heed to today and will form the central theme of what’s to follow.

In his time, Graham was concerned with the term “investor” loosely being used. The Godfather of value investing had initially defined the term investing as: “An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and a satisfactory return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative”. As markets reach new highs- participants have become increasingly imprudent, seeking higher yields and seemingly (and/or unknowingly) accepting higher risk; ultimately eroding their margin of safety. It seems now-again, the word investor is being used to describe any market participant, including and notably, crypto-mania bandwagonners. As we stand near the top of the markets, gazing into the unknown (as we’ve been doing for the past years), Graham’s concern of investor versus speculator should rightfully resurface, and more importantly; re-emphasized.

Only Time Will Tell

Semantics aside, the distinctions between investing and speculating are still debatable-and will continue in the future. Perhaps most distinctions are on the individual level, and include specific characteristics. An investor measures price in relation to intrinsic value and can close the gap between their thoughts and reality. Amazon may be a great company, but that in itself doesn’t warrant a buy. You wouldn’t pay infinite dollars for a share- but how much would you pay at this moment, given a sensible future earnings? Answering this with some degree of accuracy requires extensive intellect, financial knowledge and in-depth qualitative and quantitative analysis. Another notable trait of the investor is, as Buffett mentions, knowing your circle of competence. Other qualities include good temperament, high EQ, and patience. Although much of the rational-linked qualities are required to characterize an investor, it’s not all black and white.

Some degree of leakage occurs between investing and speculating. When facing uncertain measures; the estimation of future earnings, qualitative aspects of a business- some degree of (good) speculation may be required. For the market, benefits to speculation includes increased liquidity. As Graham puts it, theres intelligent investing and intelligent speculation, the latter has more ways of being unintelligent.

http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data/ie_data.xls

http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data/ie_data.xls

With the S&P500 seemingly blossoming from January 2009 till 2018, it’s hard to distinguish between skill and luck, after all, a rising tide lifts all boats. When the lucky sailors start to believe they have skill; that is when the danger arises- literally and figuratively. Being brutally honest with oneself could help determine if one is an investor, a speculator or a mix of both; the skillful or the lucky. The importance to distinguishing between being an investor and a speculator is essential, it may indeed help avoid financial missteps. As Mark Twain puts it: “It’s not what you know that will get you in trouble, it’s what you know that just ain’t so”. Actually, it’s more fitting to give Graham’s greatest protege, Warren Buffett, the closing act in this section: “Only when the tide goes out do you see who has been swimming naked”.

Past, Present and Uncertain Future

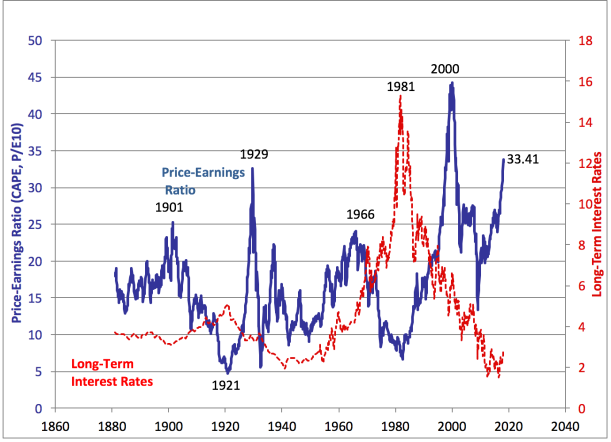

As I’m writing this, the CAPE is at its second all-time high, flirting around the 32 mark. We’ve seen elevated levels just before Black Tuesday (1929) and the dot-com bust (1999-2000) at 30 and 44, respectively. The CAPE’s average is about 16-17. Now these are just indicators- not the gospel truth ordering investors to run for the hills. However, if we are experiencing a market where assets are trading at substantial premiums, and in the past- these levels have been followed by crashes, new participants must directly or indirectly accept that “this time is different”.

http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data/ie_data.xls

The year-recent natural disasters, Korean tensions, European policies, and political uncertainties haven’t (yet) phased investor’s confidence, in large, due to the Fed suppressing interest rates for nearly a decade. Numerically, the Dow is experiencing the second longest bull market run in history, from the lows of 2009 until present, it has more than quadrupled; breaching the $26,000+ mark from its lows of $6,626. Similarly, the S&P500 has returned near 300%, from its March 2009 lows of around $680 upwards to the present $2,700 mark. The S&P 500 held a CAGR of approximately 15.7% (January 2009 till 2018) and a present price-to-earnings ratio of about 24, with a historical mean of 15. It’s unquestionably easier to double from mid 10s p/e in the early 2010s, then it would be to go 24 p/e today to 40 in the next few years.

The physical constraints of the economic reality required to sustain growth conditions certainly makes doubling the p/e again improbable, at least within the “foreseeable” future. Achieving these results would require unprecedented US and world GDP growth, federal and fiscal policies perfectly in sync with the markets, increased hourly productivity growth, multitudes of miraculous earnings, along with other combinations of inputs that would surely be within the tail ends of the probability spectrum. Climbing the mountain certainly gets harder as we close near the top. When there is upside, downside probabilities should also be addressed. As the axiom goes, there’s only a few ways things can go right, but many ways to go wrong. If Murphy’s law is even half the rule- then as t moves further on the time continuum, the risk of encountering calamities increases. Looking into the many uncertain conditions of future financial markets, and considering that “cheap money” is now a thing in the past, we should steer with greater caution and reduction of risky exposures.

Yin-Yang Outlook

• Interest Rates and inflation: The Fed is eyeing inflation closely and expects 3-4 rate hikes in 2018 to cool the expected rise in inflation. Adding a sudden surprise hike could meddle with asset prices (assuming we’ve already “correctly priced in” for 3-4 hikes). Interest rates have been extremely low, permitting higher asset valuations (in relation to bonds). Cheap debt has allowed inflated earnings and easy debt servicing. As real interest rates “return to normal”, how much will it affect earnings and repayment abilities? The sudden increase in real interest rates could collapse bond prices and simultaneously hit the equity markets. Treasury yields going up sharply (say sudden 10-year moving above 3.3-3.5%+) due to sell-off and/or over-supply (ECB, BOJ, and China slowing down on QE and/or purchasing US bonds) may trigger a turmoil.

• Rising Debt levels, US Budget Deficit and Tax Cuts: Ballooning debt has always been a central characteristic in a financial crisis. The US Total Debt is currently just over the $20 trillion mark, with a debt-to-GDP ratio reaching over 105% (increasing year-over-year since the crisis), and is expected to continue rising as a result of deficit. The increasing US budget deficit for 2018 is projected around $1 trillion. In order to fund its expenditures, Treasury states that the US will need to borrow an additional $440 billion within the next quarter. Although beneficial in the shorter term, the tax cut that decreased corporate tax from 35% to 21% will add an estimated $1.5 trillion deficit over the upcoming years. A higher deficit may constrain GDP growth over the long haul. The effects of rising deficits on the entitlements for baby-boomers remain to be seen. It seems that monetary and fiscal policies are indirectly clashing, one putting on the brakes and the other stepping on the gas in a heated economy.

• Premiums, Optimism and Risk-Appetite: With decade low interest rates, equities are trading at substantial premiums with their elevated p/e levels (along with other financial measures). This implies that future earnings will, with the help of a roaring economy and tax cuts; adequately justify today’s premium prices. The full effects of increasing interest rates on stocks remains to be seen. Wells Fargo Investor Optimism Index are nearing all time highs since the dot-com bubble. Decade long economic growth (recovery) and fiscal policies have aided the optimistic forecasts. Pro-risk behaviour is becoming increasingly common, purchasing premium equities with little to no margin of safety. The margin debt on NYSE has reached all time highs, topping $642.8B at the end of 2017 implying higher leverage and risky behaviour. With such a high margin debt, sell-offs will be amplified due to forced margin selling.

• Party, Unemployment and The Rosy Economy

The bull party, despite the recent blimp, appears to tread upward. Unemployment rate is near all-time lows, reaching and retaining 4.1% for the past few months. World economy has experienced constant growth for nearly a decade, paired with a recently strong quarterly economic report, an economic recession is unlikely within the short term (1-3 years). The recent tax cut will likely help boost short-term earnings for US companies over the next few years, so the music isn’t stopping yet. Increased repatriation is bound to pump cash positions and potential investments of US multinational corporations (within US). Although tax cuts will help artificially prolong, what Ray Dalio describes as the late stage of the debt cycle, the party cannot go on forever. Tax cuts may have short term benefits, but-there is no free lunch; costs remain to be paid in the long run.

Incerto and Amor Fati

The world is full of uncertainties. Even the “best” forecasters cannot be consistently accurate. Although the economy appears to have room to grow in the next upcoming years, there are many obstacles it must overcome, especially rising deficits constraints and rising inflation. Inflation is expected to pick up in the upcoming years, meaning that hurdle rates will increase, ultimately eroding real owner’s earnings. Other worries include political instability, rising foreign debt, war outbreaks, natural and technological disasters and shifts in market psychology that cannot be precisely quantified.

While latter worries are noteworthy, concerns should rather be on the management of payoffs in the face of rare events- negative Black Swans. These events are hard to predict and are evident only after they occur (using hindsight). The trouble with hindsight; we don’t have it until we have it. An effective weapon to combat uncertainty (if any), is not its avoidance but the proper management of risk.

A near decade of optimism warrants rising uncertainty (markets are blindsided when they are most euphoric). The looming questions and dimensions of the next financial crisis naturally begin to surface. Exact timing may be unpredictable, but it may likely include the following characteristics:

• Systematic event that will alter the way market participants (in mass) react to events; ultimately altering animal spirits

• High levels of debt, over-leverage and insolvency issues

• Unrealistic levels of optimism and delusion, a wide gap between the fundamentals of economics and finance and the mass’ perspective

The next financial meltdown may be unavoidable; investors might as well embrace their fate. Equity turmoils have always presented generous opportunities to purchase quality stocks at substantial discounts that will prove rewarding once the dust clears. Graham, should rightfully have the last words: “The intelligent investor is a realist who sells to optimists and buys from pessimists”.

Bitcoin and Crypto Mania

Since my introduction to Bitcoin in 2015 (yes, I was late), I’ve only watched it soar up, taking no trading positions. By and large, I’m a supporter of the development of global economies, notably the incorporation blockchain technology which has the ability to allow individuals in third world countries, whom don’t have enough capital; to participate in the global economy. But we are still, unfortunately, far from that. I truly hope to see a revolutionary operation that will enable participation for those in need within the distant future, not just for the betterment of the economy, but for the advancement of humankind itself.

How do we go about Bitcoin and Crypto(“currencies”)?

A currency, although a man-made concept, has a few core components which makes it valuable and desirable- or at the very least, useful. These components include stability, store of relative purchasing power, a relationship with interest rates and economic growth, which it derives from being under federal bank governance. Within the past century, the floating US Dollar has been relatively stable, especially in comparison to other currencies. The USD’s relation to interest rates (along with the net positive GDP increase) has created continuous demand for the US Dollar (foreign investments into USD). Although there are some theoretical and practical nuances, there’s a substantial benefit for a country/currency in having the ability to perform QE. Logically, there must be some government control over currency, as it can drastically improve the conditions and extensively aid in remedying poor economic growth, as experienced during the recent financial crisis.

Theory and Reality

As of present, Bitcoin, in terms of currency, lacks its core functionality (stable store of value- it’s currently too volatile) along with its convenience as a medium of exchange. The high transaction (and processing) fees makes it a costly medium of exchange. So is everyone actually using it? If cryptos were intended to be used for its intended purpose (money), then the huge influx of new users in crypto exchanges must, in theory, mean an equivalent rise in its use for practical transactions, but the reality is much different.

Do you buy your groceries, pay your utilities and taxes in Bitcoins, or other cryptos, and if you could would you? Or would you wait for someone else to buy them from you at a (hopefully) higher price? If most crypto participants are trading the “so-called-currency”, or intend to get out when it “tops”, while its rarely being used for its intended purpose as a “currency”, then its clear that we can attribute it with the concept of the greater fool. How many Bitcoin “investors” do you know who will actually use it for its intended purpose?

The Good, The Okay and The Fool

There’s a clear distinction between investing, trading, and poor speculation (what has plagued the crypto-markets). There are two main school of thoughts: fundamental analysis and technical analysis. The former embodies the definition of investing; it concerns itself with value in relation to price. Technical analysis (trading) bases itself on price and volume, in addition to other variables such as momentum. The tools required for both schools differ immensely. Fundamental analysis depends on in-depth analysis of financial statements and the comparison of intrinsic value to market price. Technical analysis concerns itself with charts, oscillators and trend analysis, in addition to price payout ratios. The tools required for poor speculation- the kind that has a clear disconnect of reality, although not a sin (yet), is wishful thinking, a four leaf clover and a lucky horseshoe. The danger is when one cannot differentiate between investors, traders and wishful thinkers. Unfortunately, the latter always thinks they’re an investor or a trader.

There are different classes of investments: assets, commodities, rare goods, and currencies:

• Assets: the valuation assets are fundamentals driven. To invest, we must rationally value the asset- a popular measure would be a form of discounted cash flow (that is, the intrinsic value of the discounted cash flow of the company from now till judgement day). Cryptocurrencies don’t produce anything (no earnings), therefore cannot be rationally valued and therefore (by way of logic) cannot be considered an investment.

• Commodities: are complex in their valuations, they derive their price from economic models of supply and utilitarian demand. These goods are essential to daily activities (energy-related commodities; gas, oil, wheat, etc.). An argument for Bitcoin (and some cryptos) is that it is equivalent to gold reserves, making it a commodity/currency (comparable pricing). It shares the same theoretical properties of gold: alternative “store of value”, derives its demand from perceived utility. Although gold has real usage (conductor and jewelry), the aggregate supply of gold does not equate to its aggregate utility; the physical usages are negligible. Gold, like Bitcoin produces nothing; so has no actual intrinsic value. It is true that Bitcoin and gold have abstract similarities, but only in a vacuum. The price volatility of Bitcoin and cryptos renders it an unreliable gold-alternative.

• Rare goods: are priced by its demand which derives from perceived market value and scarcity, think in terms antiques and classic cars. Cryptocurrencies are not rare goods. The argument of its limited supply is fallacious. Bitcoin may be limited in supply, but that in itself doesn’t make it valuable; there’s also a limited supply of 1998 mint-condition Pikachu Pokemon cards.

• Currencies: the price of a currency is determined by supply and demand in relation (as stated earlier) to its relative purchasing power, stable store of value, and medium of exchange. As previously noted, cryptocurrencies do not effectively qualify for the definition of a “successful” currency.

Another argument for the fundamental value of Bitcoin is using Metcalfe’s Law (originally used in telecom). This argument is widely misinterpreted. Metcalfe’s Law states that the value of a network roughly equates to the squared number of users or nodes on the network. The argument is that as more users join the cryptocurrency markets, its price increase may be justified because of utility demand. The application of Metcalfe’s Law on Bitcoin (and other cryptos) is erroneous. A user is defined as an individual who uses the network as intended, in this case, an individual who uses Bitcoin to make transactions. There’s a clear difference between a user and an open account/ speculator/ trader; this is where Metcalfe’s Law breaks down.

It is evident that fundamentals are unclear and much uncertainty remains (how will it be incorporated efficiently into daily activities? What are its impact on the economy and fiat currency?). This is not to say that money cannot be made from the crypto mania. The proper approach is to implore technical analysis. For experienced institutional traders (and the few “good” retail traders), there are merits in trading cryptocurrencies, however, the small-fry crypto fanatics should be discouraged to do so.

It’s not immoral to poorly speculate and bet on something you don’t fully understand, it is however- illogical. Speculating and gambling (in small sums) may, with low probabilities, be rewarding. Bachelier puts it lightly: “the mathematical expected value of a speculator is zero”, for the poor speculators (in aggregate); it’s permanent loss. After all, there are widespread stories of individuals whom have made large sums betting on Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies. Consequently, there are plenty more crypto bets that have ended thinning out the pockets, but are ignored due to selective biases (such as the survivorship bias).

Euphoria, delusion, FOMO have plagued the crypto-markets. In aggregate, many cryptocurrencies today will cease to exist in due time, the practical constraints cannot allow for 1000+ cryptocurrencies to all successfully integrate within society (this is not to say that a few cannot become successful). Consequently, amateur crypto traders will lose money- especially with the widespread fraud and poorly placed exchange regulations (pump and dumps, etc.). To reiterate, there’s a distinction between a professional trader and a foolish speculator. Likewise, there’s difference between skill and luck, if you’re lucky, best admit before you’re caught swimming naked.

Encore:

• Blockchain implementations have the potential to drastically improve lives of those who cannot participate in the current global economy

• Blockchain technology and applications are independent from and not limited to cryptocurrencies

• There’s a disconnect between theory and practice, closing it may move cryptocurrencies closer to its intended use (it needs legitimate users, not traders or gamblers, it needs actual daily activities transaction; it must have utilitarian demand, or else it’s basically worthless)

• For Bitcoin to succeed as a currency, it must be globally accepted, but why not accept other cryptos that have better transaction and superior design (Ethereum’s smart contract, Litecoin’s transaction)? Why pay in Bitcoin when you can pay in Ethereum, or Dogecoin for that matter? Who wants to be paid in Kodakcoin? (Rhetoric).

• Bitcoin and Cryptocurrencies in aggregate cannot be rationally valued; there’s a difference between valuing and pricing

• This is not to say that skilled traders should not trade it- fundamental analysis is inapplicable, but technical analysis may have some success

• Cryptos are a trader’s game, not fundamentally driven; unfortunately, most participants lack technical analysis knowledge and tools (institutional grade algorithms), and without a doubt, suffers from the effects of “the greater fool”

Recommended books: Blockchain Revolution by Alex Tapscott and Don Tapscott, and The Age of Cryptocurrency by Michael J. Casey and Paul Vigna.

After[thoughts]1

La Vita è Bella

For those who take the time to read my collection of thoughts, I am truly appreciative – thank you. Further, I must apologize for my absence. I still read religiously, now more than ever and I’ve added science, physics and mathematics into my arsenal. Originally, I only took interest in business and investing related-matters, but learning other subjects has profoundly enriched my thoughts and conditioned a more multi-dimensional analysis system. Having the ability of viewing the world through different lenses really enriches the experience that makes life. Seeing the world differently, particularly from a physics viewpoint, helps us appreciate the beauty of reality.

Life is a lot more beautiful, once you realize that the Big Bang had to happen, stars died to form the gas clouds enabling our solar system to rise from it’s cosmic ashes, atoms came together in an exact mixture at the perfect time to form everything we presently know to be life. A mathematical view would indicate that the odds are as close as ever to 0; life truly is the greatest Black Swan event. A thrilling phenomena when you really think about it.

Never would I had viewed the world in such light if I hadn’t stumbled upon Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Astrophysics for People in a Hurry– this sparked my interest in science and physics. It’s an exciting feeling to pick up a book knowing that in some way- you’ll expand you’re circle of competence. Whether it’s finance and its strategic investments, or physics and its journey for truth2, learning adds to the aggregate knowledge of mankind. Books allow knowledge to dissipate from one generation to the next. It’s a magnificent learning tool, allowing individuals to absorb the knowledge of an author’s lifetime of laborious work within days. Time travelling of the mind and ideas are all made possible through the vehicle of a book. As Carl Sagan stated: “…one glance at it and you’re in the mind of another person, maybe somebody dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, an author is speaking clearly and silently inside your head, directly to you. Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people who never knew each other, citizens of distant epochs. Books break the shackle of time. A book is proof that humans are capable of working magic…”

The pleasure lies not in discovering the truth, but in searching for it.

-Leo Tolstoy

Reflections

Other than exhausting my time scavenging through the markets or pondering about the cosmos, I have abstract thoughts that have occupied my mind; 3 contemplations to be exact.

1. Risk, uncertainty and complex models

2. The disconnect between perspective and reality

3. Evolution of financial theories

1. Risk, Uncertainty and Complex Models

The distinction between risk and uncertainty is crucial. Risk is when the outcomes are known with reasonable precision but remain to be seen. It can be mathematically calculated to a probable number; think for instance rolling a dice. The outcomes are known, picking a number from 1 to 6, the probability of landing on it is 1/6 (16.7%). So, if you bet money on, say number 1, there’s an 83.33% chance you will lose your money. Uncertainty reflects the unknown; some of the outcomes may be known, but the probabilities of occurrences are vague or extensively unpredictable.

Transforming qualitative information to quantitative probabilities entails human error and biases. The dilemma is believing that all uncertainties are known; refining mathematical models which exclude unknown events (or removing outliers) and heavily weighing on them for guidance as seen in financial forecasting.

Under risk, complex models are very useful, as all possibilities are known. In uncertainty, complex models do not provide a good basis for the true value. As Gerd Gigerenzer says “the best decision making under risk is not the best decision making under uncertainty”. Complex problems do not always require complex solutions.

Risk management; decreasing risky exposures and increasing risk absorption abilities, sticking with simple heuristics (ie. index funds), and defining your circle of competence are best practices against uncertainty.

(1) How will true mu be determined under uncertainty? Will it ever? (2) Or will it always be the cosmic standard that one can only profit bearing some degree of uncertainty?

2. The Disconnect Between Perspective and Reality

In 1996, Greenspan pondered: “…But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade?”. Four years later, the tech-bubble burst and the NASDAQ came crashing down over the following two years, eradicating nearly three quarters off its peak. Optimism may be good for health, but should be cautioned when paired in decision-making. Robert Shiller, Nobel Laureate describes euphoric phenomenas well (read this paper); “When speculative prices go up creating success for some investors, this may attract public attention, promote mouth-to-mouth enthusiasm, and heighten expectations for further price increases…high prices are ultimately not sustainable, since they are only high because of expectations of further price increases…”.

Financial ruins stem from overly-optimistic predictions but is mainly rooted in a disassociation between perceived views and reality. Blind mass perception can sway the markets into overly optimistic or pessimistic territories, but only for so long; the realistic constraints of economics and finance will readapt and regain rationality over the long run. Optimism overrides caution, suppresses rationality while boosting confidence, pitting investors into what Daniel Kahneman describes as the planning fallacy; when planning we always think we are right and overweight the best case scenarios. A method to detach from possible biases is by reasoning from first principles. This involves breaking down problems to the most fundamental truth and then building solutions and decision-making from these indisputable truths.

For instance, we have many forms of transportation; walking, bicycles, vehicles, helicopters, airplanes and boats. The core function of transportation is to go from point A to B in the safest and most time-efficient manner (aesthetics aside). So what’s the best way of doing that in theory? Teleportation, and since that’s not achievable on a human scale (yet), Elon Musk’s Hyperloop will have to do for now.

Reasoning up from first principles in investing is much more complex; as human-made concept, it strays from physics and mathematical laws (what is universally true- ie. gravity, Pi, etc.). Musk says that most people reason from analogy rather than first principles – this phenomena is especially widespread in finance. Many market participants buy or sell holdings based on someone else’s prediction (think cryptos) or because prevailing market sentiments indicate a bearish trend. They forget that the price is the underlying reflection of the fundamentals of a company. Profit can be made by following trends, but if following is purely based on reasoning by analogy (buying because others are), then it becomes dangerous. This leads to widespread euphoria resulting in the formation of bubbles, and its usually original thinkers, those who reason correctly from fundamental analysis; the first principles of investing, that fare better coming out of meltdowns.

3. Evolution of Financial Theories

The history of finance was heavily shaped by economists, statisticians, and individuals who dedicated their lives to their work which will be forever archived within finance. From Bachelier, to Fisher, Graham, to Black, Fama, Jensen…Shiller, to Thaler’s behavioural economics, there’s been a constant refinement of principles. Many theories built off the work of old ones. For instance Paul Samuelson refined and shed light on Louis Bachelier’s asset pricing model in his thesis “Theory of Speculation”(Théorie de la Spéculation) which serves as the foundation for quantitative finance today (EMH, Black-Scholes, etc.). Even more interesting is the leakage between finance and physics, or the reverse. Bachelier’s model had actual confirmed Brownian Motion, years before Albert Einstein’s paper: Investigation on the Theory of Brownian Motion. Fascinatingly, Bachelier turned to physics and used a function of heat diffusion and central limit theorem principles in the making of his work.

Perhaps in the near future, there will be theories that incorporate physics and current fundamental, technical and behavioural analysis (with less controversy amongst scholars). Perhaps this new pricing model or grand financial theory will be to finance what string theory is to quantum physics.

Fin

And now, reader, it is time to part – thank you again for reading my thoughts. Let me finish by borrowing from The Pilgrim’s Progress as the Old-Valiant-for Truth in his journey; my sword1, I give to him that shall succeed me in my pilgrimage2.